In this series, we learn more about what inspired our talented graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, what brought them to their field of study, and the questions that drive their work at the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC). Responses are edited for clarity and length.

Caleb Geissler is a fifth year PhD student in Chemical and Biological Engineering in Christos Maravelias’ lab at Princeton University. With projects ranging from supply chain optimization to studying biofuels and carbon capture and storage on a national scale, his work generally centers on the application of mathematical optimization to renewable energy systems and sustainability.

Tell me about your favorite project

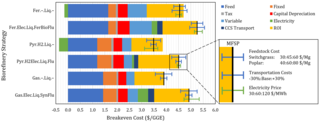

I'd say a recent favorite is a paper that came out recently in Nature Energy. We used a lot of satellite data to survey the individual fields where we could theoretically plant biomass. We had data for more than 50,000 fields in the Midwest and we used it to answer many different kinds of questions. Where would you put biorefineries? How big should they be? What technologies should you use to convert that biomass into fuel, because there are a lot of different options. And each of those options comes with different options for carbon capture. We combined supply chain design with biorefinery design, and we did this large-scale analysis in this eight state region in the Midwest to show how things change as you prioritize different objectives.

What did your academic path look like?

I started doing very basic research on renewable fuels in high school. My high school – John Adams high school in South Bend, Indiana – had this science research program. It wasn't that in-depth, but I was introduced to the idea of biofuels. And then in undergrad (at Purdue University), I did experimental research with microalgae to make biofuels. Within a few years, I realized that I didn't love doing research in the lab. Later, I did a summer research experience at Michigan State University with the GLBRC in Eric Heggs’ lab working on electrocatalytic lignin valorization . Through that, I was put in touch with my current advisor, Christos Maravelias, when he was still at UW-Madison. I read up on his work and thought, I love the topic and since its computational work I wouldn’t have to deal with equipment failures in a lab. It would be interesting to study these things at a higher level. I joined his lab and was at UW–Madison for a year, and then our whole lab moved to Princeton. Funnily enough it means that I have done GLBRC research at Michigan State, Wisconsin, and Princeton.

Avoiding catastrophic climate events and working towards a more sustainable future is probably what gets me the most motivated to work in this field.... Definitely just trying to make sure we can still survive on this planet.

Caleb Geissler

What inspired your passion for science?

When I was a little kid, I really loved math and numbers, so I wanted to be a math teacher. And then an accountant. Around sixth grade I started to love chemistry and decided that I wanted to be a chemical engineer. I had no idea what chemical engineering was, I just liked chemistry and math. What I found out is that there's not that much chemistry in chemical engineering, but there's enough math that I enjoy it. I think I've always been attracted to science in general, and engineering felt like a good way to combine that with a lot of math.

What brings you the most joy in your work?

Something I enjoy a lot is data visualization. I'm in a field where you have a lot of data you want to present in papers in a limited number of figures. So you have to really cram in as much information as you can. That is its own little problem to figure out… which I find very enjoyable.

You’ve worked a lot with carbon capture and sustainability, is that what inspires your interest in your work?

Yeah, I think it's not necessarily the CO2 capture itself that has my interest. Avoiding catastrophic climate events and working towards a more sustainable future is probably what gets me the most motivated to work in this field. Within my choice of research field, obviously, the type of research has varied a lot. But in terms of choice of field… definitely just trying to make sure we can still survive on this planet.

How do you apply your sustainability research to your day to day life?

I’m a graduate student, so it's not like I have a whole lot of spare money lying around. I'm at the stage of my life that’s more thinking about them rather than being able to implement things. I try to be as sustainable as I can, you know: don't eat as much meat, avoid starting forest fires. When I was looking at getting a car, making sure it was a hybrid (because I can't afford an EV). Living close enough to where I work so that I can walk or bike instead of having to drive every day you know, things like that.

How do you see the real world affecting your work?

Biofuels won’t succeed without policy support. Before they updated the Inflation Reduction Act, politicians were talking about what the new tax credit should be, so a lot of our research was looking at what different credits would mean for these biofuels. There's a higher credit for sustainable aviation fuel than there is for renewable gasoline and diesel. I’ve studied the implementation of these credits on a national level. We asked, are these credits good enough to do what we want? If they weren't — which, in some cases is true — what would need to change?

What do you like to do outside of work?

Generally sports and board games. At Princeton we have a summer softball league where different departments play a couple times a week. I play spike ball once a week; that's my favorite one. As with every other American, I’m getting much more into Pickleball. I'm also an avid player of Dungeons and Dragons. Right after the pandemic started, I started a campaign with some of my friends in Wisconsin. We just finished two months ago. That's been like a part time job for the past four years, coming up with insanely elaborate puzzles. I did a lot of things like writing riddles and prophecies, planning elaborate puzzles and building an entire world, but sometimes they would blow up everything and I would have to plan the next two and a half hours on the fly.

What do you think you learned from Dungeon Mastering?

Two things come to mind. One is just getting much better at dealing with scheduling and logistics. We’re all graduate students, so we're all really busy. And they're all in Wisconsin, so different time zones. On a more personal note, I want to have fun. I also have to make sure other people are having fun. It’s a very healthy experience of intentionally thinking about other people and what would benefit them and what they would find fun. It’s also very humbling when I come up with things and then they do something completely different and it ends up being way better than anything I could have come up with. The improvisation required feels very healthy for my brain.

What advice do you have for future researchers?

In terms of choosing research fields, especially if you're going into a PhD, choose something you absolutely love. If you don't start a PhD in something that you love, you will be miserable. It is always better to do something that you're really passionate about. And then if you get stuck doing that for five years, by the end, you might lose some of that passion, but at least it's easier to get that work done.

I would recommend to anyone in any research field to just learn to code. I code all the time. In most research, you're going to be analyzing data, making figures, repeating tasks over and over again that can be automated. To have things that can be done automatically saves you so much time, which is very important. We just don't have that much time to get everything done.