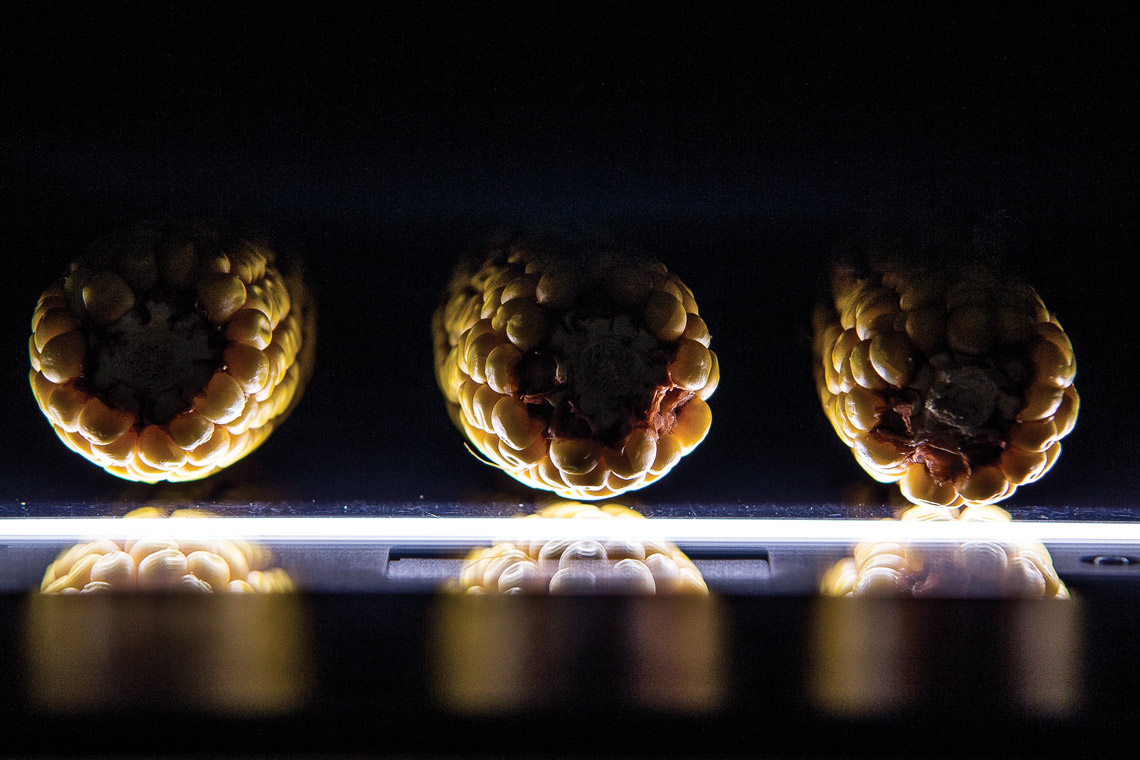

In a back room in the university’s Seeds Building, researchers scan ears of corn—three at a time—on a flatbed scanner, the kind you’d find at any office supply store. After running the ears through a shelling machine, they image the de-kerneled cobs on a second scanner.

The resulting image files—up to 40 gigabytes’ worth per day—are then run through a custom-made software program that outputs an array of yield-related data for each individual ear. Ultimately, the scientists hope to link this type of information—along with lots of other descriptive data about how the plants grow and what they look like—back to the genes that govern those physical traits. It’s part of a massive national effort to deliver on the promise of the corn genome, which was sequenced back in 2009, and help speed the plant breeding process for this widely grown crop.

“When it comes to crop improvement, the genotype is more or less useless without attaching it to performance,” explains Bill Tracy, professor and chair of the Department of Agronomy. “The big thing is phenotyping—getting an accurate and useful description of the organism—and connecting that information back to specific genes. It’s the biggest thing in our area of plant sciences right now, and we as a college are playing a big role in that.”

No surprise there. Since the college’s founding, plant scientists at CALS have been tackling some of the biggest issues of their day. Established in 1889 to help fulfill the University of Wisconsin’s land grant mission, the college focused on supporting the state’s fledgling farmers, helping them figure out how to grow crops and make a living at it. At the same time, this practical assistance almost always included a more basic research component, as researchers sought to understand the underlying biology, chemistry and physics of agricultural problems.

That approach continues to this day, with CALS plant scientists working to address the ever-evolving agricultural and natural resource challenges facing the state, the nation and the world. Taken together, this group constitutes a research powerhouse, with members based in almost half of the college’s departments, including agronomy, bacteriology, biochemistry, entomology, forest and wildlife ecology, genetics, horticulture, plant pathology and soil science.

“One of our big strengths here is that we span the complete breadth of the plant sciences,” notes Rick Lindroth, associate dean for research at CALS and a professor of entomology. “We have expertise across the full spectrum—from laboratory to field, from molecules to ecosystems.”

This puts the college in the exciting position of tackling some of the most complex and important issues of our time, including those on the applied science front, the basic science front—and at the exciting new interface where the two approaches are starting to intersect, such as the corn phenotyping project.

“The tools of genomics, informatics and computation are creating unprecedented opportunities to investigate and improve plants for humans, livestock and the natural world,” says Lindroth. “With our historic strength in both basic and applied plant sciences, the college is well positioned to help lead the nation at this scientific frontier.”

It’s hard to imagine what Wisconsin’s agricultural economy would look like today without the assistance of CALS’ applied plant scientists.

The college’s early horticulturalists helped the first generation of cranberry growers turn a wild bog berry into an economic crop. Pioneering plant pathologists identified devastating diseases in cabbage and potato, and then developed new disease-resistant varieties. CALS agronomists led the development of the key forage crops—including alfalfa and corn—that feed our state’s dairy cows.

Fast-forward to 2015: Wisconsin is the top producer of cranberries, is third in the nation in potatoes and has become America’s Dairyland. And CALS continues to serve the state’s agricultural industry.

The college’s robust program covers a wide variety of crops and cropping systems, with researchers addressing issues of disease, insect and weed control; water and soil conservation; nutrient management; crop rotation and more. The college is also home to a dozen public plant-breeding programs—for sweet corn, beet, carrot, onion, potato, cranberry, cucumber, melon, bean, pepper, squash, field corn and oats—that have produced scores of valuable new varieties over the years, including a number of “home runs” such as the Snowden potato, a popular potato chip variety, and the HyRed cranberry, a fast-ripening berry designed for Wisconsin’s short growing season.

While CALS plant scientists do this work, they also train the next generation of researchers—lots of them. The college’s Plant Breeding and Plant Genetics Program, with faculty from nine departments, has trained more graduate students than any other such program in the nation. Just this past fall, the Biology Major launched a new plant biology option in response to growing interest among undergraduates.

“If you go to any major seed company, you’ll find people in the very top leadership positions who were students here in our plant-breeding program,” says Irwin Goldman PhD’91, professor and chair of the Department of Horticulture.

Among the college’s longstanding partnerships, CALS’ relationship with the state’s potato growers is particularly strong, with generations of potato growers working alongside generations of CALS scientists. The Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association (WPVGA), the commodity group that supports the industry, spends more than $300,000 on CALS-led research each year, and the group helped fund the professorship that brought Jeff Endelman, a national leader in statistical genetics, to campus in 2013 to lead the university’s potato-breeding program.

“Research is the watchword of the Wisconsin potato and vegetable industry,” says Tamas Houlihan, executive director of the WPVGA. “We enjoy a strong partnership with CALS researchers in an ongoing effort to solve problems and improve crops, all with the goal of enhancing the economic vitality of Wisconsin farmers.”

Over the decades, multi-disciplinary teams of CALS experts have coalesced around certain crops, including potato, pooling their expertise.

“Once you get this kind of core group working, it allows you to do really high-impact work,” notes Patty McManus, professor and chair of the Department of Plant Pathology and a UW–Extension fruit crops specialist.

CALS’ prowess in potato, for instance, helped the college land a five-year, $7.6 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to help reduce levels of acrylamide, a potential carcinogen, in French fries and potato chips. The multistate project involves plant breeders developing new lines of potato that contain lower amounts of reducing sugars (glucose and fructose) and asparagine, which combine to form acrylamide when potatoes are fried. More than a handful of conventionally bred, low-acrylamide potato varieties are expected to be ready for commercial evaluations within a couple of growing seasons.

“It’s a national effort,” says project manager Paul Bethke, associate professor of horticulture and USDA-ARS plant physiologist. “And by its nature, there’s a lot of cross-talk between the scientists and the industry.”

Working with industry and other partners, CALS researchers are responding to other emerging trends, including the growing interest in sustainable agricultural systems.

“Maybe 50 years ago, people focused solely on yield, but that’s not the way people think anymore. Our crop production people cannot just think about crop production, they have to think about agroecology, about sustainability,” notes Tracy. “Every faculty member doing production research in the agronomy department, I believe, has done some kind of organic research at one time or another.”

Embracing this new focus, over the past two years CALS has hired two new assistant professors—Erin Silva, in plant pathology, who has responsibilities in organic agriculture, and Julie Dawson, in horticulture, who specializes in urban and regional food systems.

“We still have strong partnerships with the commodity groups, the cranberries, the potatoes, but we’ve also started serving a new clientele—the people in urban agriculture and organics that weren’t on the scene for us 30 years ago,” says Goldman. “So we have a lot of longtime partners, and then some new ones, too.”

Working alongside their applied colleagues, the college’s basic plant scientists have engaged in parallel efforts to reveal fundamental truths about plant biology—truths that often underpin future advances on the applied side of things.

For example, a team led by Aurélie Rakotondrafara, an assistant professor of plant pathology, recently found a genetic element—a stretch of genetic code—in an RNA-based plant virus that has a very useful property. The element, known as an internal ribosome entry site, or IRES, functions like a “landing pad” for the type of cellular machine that turns genes—once they’ve been encoded in RNA—into proteins. (A Biology 101 refresher: DNA—>RNA—>Protein.)

This viral element, when harnessed as a tool of biotechnology, has the power to transform the way scientists do their work, allowing them to bypass a longstanding roadblock faced by plant researchers.

“Under the traditional mechanism of translation, one RNA codes for one protein,” explains Rakotondrafara. “With this IRES, however, we will be able to express several proteins at once from the same RNA.”

Rakotondrafara’s discovery, which won an Innovation Award from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) this past fall and is in the process of being patented, opens new doors for basic researchers, and it could also be a boon for biotech companies that want to produce biopharmaceuticals, including multicomponent drug cocktails, from plants.

Already, Rakotondrafara is working with Madison-based PhylloTech LLC to see if her new IRES can improve the company’s tobacco plant-based biofarming system.

“The idea is to produce the proteins we need from plants,” says Jennifer Gottwald, a technology officer at WARF. “There hasn’t been a good way to do this before, and Rakotondrafara’s discovery could actually get this over the hump and make it work.”

While Rakotondrafara is a basic scientist whose research happened to yield a powerful application, CALS has a growing number of scientists—including those involved in the corn phenotyping project—who are working at the exciting new interface where basic and applied research overlap. This new space, created through the mind-boggling advances in genomics, informatics and computation made in recent years, is home to an emerging scientific field where genetic information and other forms of “big data” will soon be used to guide in-the-field plant-breeding efforts.

Sequencing the genome of an organism, for instance, “is almost trivial in both cost and difficulty now,” notes agronomy’s Bill Tracy. But a genome—or even a set of 1,000 genomes—is only so helpful.

What plant scientists and farmers want is the ability to link the genetic information inside different corn varieties—that is, the activity of specific genes inside various corn plants—to particular plant traits observed in the greenhouse or the field. The work of chronicling these traits, known as phenotyping, is complex because plants behave differently in different environments—for instance, growing taller in some regions and shorter in others.

“That’s one of the things that the de Leon and Kaeppler labs are now moving their focus to—massive phenotyping. They’ve been doing it for a while, but they’re really ramping up now,” says Tracy, referring to agronomy faculty members Natalia de Leon MS’00 PhD’02 and Shawn Kaeppler.

After receiving a large grant from the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center in 2007, de Leon and Kaeppler decided to integrate their two research programs. They haven’t looked back. With de Leon’s more applied background in plant breeding and field evaluation, plus quantitative genetics, and with Kaeppler’s more basic corn genetics expertise, the two complement each other well. The duo have had great success securing funding for their various projects from agencies including the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Energy.

“A lot of our focus has been on biofuel traits, but we measure other types of economically valuable traits as well, such as yield, drought tolerance, cold tolerance and others,” says Kaeppler. Part of the work involves collaborating with bioinformatics experts to develop advanced imaging technologies to quantify plant traits, projects that can involve assessing hundreds of plants at a time using tools such as lasers, drone-mounted cameras and hyperspectral cameras.

This work requires a lot of space to grow and evaluate plants, including greenhouse space with reliable climate control in which scientists can precisely measure the effects of environmental conditions on plant growth. That space, however, is in short supply on campus.

“A number of our researchers have multimillion-dollar grants that require thousands of plants to be grown, and we don’t always have the capacity for it,” says Goldman.

That’s because the Walnut Street Greenhouses, the main research greenhouses on campus, are already packed to the gills with potato plants, corn plants, cranberries, cucumbers, beans, alfalfa and dozens of other plant types. At any given moment, the facility has around 120 research projects under way, led by 50 or so different faculty members from across campus.

Another bottleneck is that half of the greenhouse space at Walnut Street is old and sorely outdated. The facility’s newer greenhouses, built in 2005, feature automated climate control, with overlapping systems of fans, vents, air conditioners and heaters that help maintain a pre-set temperature. The older houses, constructed of single-pane glass, date back to the early 1960s and present a number of challenges to run and maintain. Some don’t even have air conditioning—the existing electrical system can’t handle it. Temperatures in those houses can spike to more than 100 degrees during the summer.

“Most researchers need to keep their plants under fairly specific and constant conditions,” notes horticultural technician Deena Patterson. “So the new section greenhouse space is in much higher demand, as it provides the reliability that good research requires.”

To help ameliorate the situation, the college is gearing up to demolish the old structures and expand the newer structure, adding five more wings of greenhouse rooms, just slightly north of the current location—out from under the shadow of the cooling tower of the West Campus Co-Generation Facility power plant, which went online in 2005. The project, which will be funded through a combination of state and private money, is one of the university’s top building priorities.

Fortunately, despite the existing limitations, the college’s plant sciences research enterprise continues apace. Kaeppler and de Leon, for example, are involved in an exciting phenotyping project known as Genomes to Fields, which is being championed by corn grower groups around the nation. These same groups helped jump-start an earlier federal effort to sequence the genomes of many important plants, including corn.

“Now they’re pushing for the next step, which is taking that sequence and turning it into products,” says Kaeppler. “They are providing initial funding to try to grow Genomes to Fields into a big, federally funded initiative, similar to the sequencing project.”

It’s a massive undertaking. Over 1,000 different varieties of corn are being grown and evaluated in 22 environments across 13 states and one Canadian province. Scientists from more than a dozen institutions are involved, gathering traditional information about yield, plant height and flowering times, as well as more complex phenotypic information generated through advanced imaging technologies. To this mountain of data, they add each corn plant’s unique genetic sequence.

“You take all of this data and just run millions and billions of associations for all of these different traits and genotypes,” says de Leon, who is a co-principal investigator on the project. “Then you start needing supercomputers.”

Once all of the dots are connected—when scientists understand how each individual gene impacts plant growth under various environmental conditions—the process of plant breeding will enter a new sphere.

“The idea is that instead of having to wait for a corn plant to grow for five months to measure a certain trait out in the field, we can now take DNA from the leaves of little corn seedlings, genotype them and make decisions within a couple of weeks regarding which ones to advance and which to discard,” says de Leon. “The challenge now is how to be able to make those types of predictions across many environments, including some that we have never measured before.”

To get to that point, notes de Leon, a lot more phenotypic information still needs to be collected—including hundreds and perhaps thousands more images of corn ears and cobs taken using flatbed scanners.

“Our enhanced understanding of how all of these traits are genetically controlled under variable environmental conditions allows us to continue to increase the efficiency of plant improvement to help meet the feed, food and fiber needs of the world’s growing population,” she says.

The Bigger Picture

Crop breeders aren’t the only scientists doing large-scale phenotyping work. Ecologists, too, are increasingly using that approach to identify the genetic factors that impact the lives of plants, as well as shape the effects of plants on their natural surroundings.

“Scientists are starting to look at how particular genes in dominant organisms in an environment—often trees—eventually shape how the ecosystem functions,” says entomology professor Rick Lindroth, who also serves as CALS’ associate dean for research. “Certain key genes are driving many fantastically interesting and important community- and ecosystem-level interactions.”

How can tree genes have such broad impacts? Scientists are discovering that the answer, in many cases, lies in plant chemistry.

“A tree’s chemical composition, which is largely determined by its genes, affects the community of insects that live on it, and also the birds that visit to eat the insects,” explains Lindroth. “Similarly, chemicals in a tree’s leaves affect the quality of the leaf litter on the ground below it, impacting nutrient cycling and nitrogen availability in nearby soils.”

A number of years ago Lindroth’s team embarked on a long-term “genes-to-ecosystems” project (as these kinds of studies are called) involving aspen trees. They scoured the Wisconsin landscape, collecting root samples from 500 different aspens. From each sample, they propagated three or four baby trees, and then in 2010 planted all 1,800 saplings in a so-called “common garden” at the CALS-based Arlington Agricultural Research Station.

“The way a common garden works is, you put many genetic strains of a single species in a similar environment. If phenotypic differences are expressed within the group, then the likelihood is that those differences are due to their genetics, not the environment,” explains Lindroth.

Now that the trees have had some time to grow, Lindroth’s team has started gathering data about each tree—information such as bud break, bud set, tree size, leaf shape, leaf chemistry, numbers and types of bugs on the trees, and more.

Lindroth and his partners will soon have access to the genetic sequence of all 500 aspen genetic types. Graduate student Hilary Bultman and postdoctoral researcher Jennifer Riehl will do the advanced statistical analysis involved—number crunching that will reveal which genes underlie the phenotypic differences they see.

In this and in other projects, Lindroth has called upon the expertise of colleagues across campus, developing strategic collaborations as needed. That’s easy to do at UW–Madison, notes Lindroth, where there are world-class plant scientists working across the full spectrum of the natural resources field—from tree physiology to carbon cycling to climate change.

“That’s the beauty of being at a place like Wisconsin,” Lindroth says.