As she walked through a corn maze at Utah’s annual Cornbelly festival, something distracted Dalia Habib from the festivities and fried food: corn stalks and kernels littered the ground.

It made her wonder if there was a better use for these natural resources.

“At the end of the day there’s just so much being wasted,” she said. “Not just at festivals, but all around the world.”

She turned to the internet, where she found the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, a federally-funded center based at the University of Wisconsin–Madison where scientists are working to make economically and environmentally sustainable fuels and products from non-food plants.

Inspired, she figured out a way to brew her own cellulosic biofuel.

Unlike GLBRC researchers, Habib didn’t have access to a university lab. She didn’t have a PhD, nor even a high school diploma. The middle schooler from Salt Lake City did have a kitchen, a couple of willing relatives, and an abiding love for science.

A finalist in the 2024 Thermo Fisher Scientific Junior Innovators Challenge, Habib isn’t the sort of 13-year-old who waits around for someone to teach her. If she wants to know something, she’s going to learn it. When she missed the sign up for dance club, she studied jazz and hip hop moves in her room. Since her school doesn’t offer Arabic or Japanese, she takes lessons on Duolingo so she can chat with her family and friends.

Before discovering GLBRC, Habib assumed that all the fuel we put in our gas tanks came from fossil fuels, which she knows are a huge contributor to climate change. Climate change isn’t just drying lakes and increasing global temperatures; many of her friends have asthma, a chronic lung disease on the rise thanks to air pollution.

Reading three or four hours every day through research articles and methods sections, Habib designed a project she could do in her kitchen.

Cellulase, she bought off Amazon. Centrifuges and glucose meters, she borrowed from relatives who work in labs. And for the fermenting process, she used Fleischmann’s yeast.

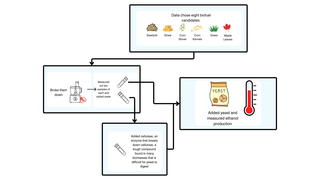

Habib chose eight types of biomass – including sawdust, straw, leaves, grass, and corn. She ground them up in a food processor and boiled the powder. She treated half the samples with cellulase, a cocktail of enzymes that break down cellulose into simpler forms of sugar, then used yeast to ferment them for 24 hours.

Habib found that sources with higher sugar content, such as sugar cane and corn kernels, had the highest ethanol yields, particularly when treated with enzymes.

“This project highlights the importance of recycling biomass materials,” Habib wrote of her findings. “Biomass contains sugar from the photosynthesis process which can be converted to renewable liquid fuels (biofuel).”

Habib’s experiment highlights a problem scientists have spent decades trying to solve. To turn plant fibers into biofuels, you first have to break them down into components that microbes can digest.

Pretreatment is often a combination of mechanical and chemical processes — grinding up the biomass and subjecting it to some combination of heat and solvent. This typically removes lignin, a complex part of the cell wall that provides strength, and leaves the other two primary components, cellulose and hemicellulose.

Most microbes can’t digest these polymers, so the long chains of molecules need to be broken down into simpler fermentable sugars (glucose and xylose), a process known as hydrolysis. There are chemicals that can dissolve cellulose, but they can create toxic conditions that inhibit fermentation.

That's where enzymes come in.

“Enzymes digest pretty much everything that's made biologically,” said Brian Fox, a professor of biochemistry at UW–Madison and member of GLBRC who studies enzymes. “They work under physiological conditions. They don’t damage the chemical composition of the cellulose in ways that acids or other kinds of ionic liquids may ... because it's natural.”

But enzymatic hydrolysis is also expensive; enzymes are one of the biggest costs of biorefinery operations.

That's why scientists at GLBRC and other bioenergy research centers are working to develop better pretreatment technologies such as γ-valerolactone (GVL), which uses plant-derived solvents, and reductive catalytic fractionation (RCF), a process that makes it easier to extract valuable products from lignin.

Fox said Habib's experiment is a simple demonstration of the concepts behind enzymatic hydrolysis.

“That was a nice, nice experiment she put together,” he said. “I mean, it would not have looked unlike a lot of experiments had been done in the last 20 years on cellulase, and the result wouldn't look all that different either, actually, so good for her.”

As much as she loved doing the project, her favorite part was presenting it.

“Doing the work is really good itself, and it's amazing,” Habib said. “But I don't think it really means anything if you can't express your work and share it with others. You can't do it all by yourself. You have to collaborate and work with others.”

Now an eighth grader, Habib is a little nervous about starting high school, but she’s also excited.

“I just like learning about how the world works as a whole,” she said. “It just really fascinates me.”

When she grows up, Habib wants to tackle some of those climate issues that have her worried and is particularly interested in pursuing environmental engineering. But Habib isn’t the type to wait a decade for a college degree to jump in feet first.

“I'm like thirteen,” she said, “I’m not Albert Einstein, but if I put my mind to something, then I can do it.”