Scientists have long eyed switchgrass as a promising and sustainable source of fuels that can replace gasoline and other petroleum products. New research shows the plant can help slow climate change, but only if grown on the right lands.

A new study by researchers at the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center found switchgrass grown on abandoned farm fields and other marginal lands in Michigan could produce enough biofuel to cut annual greenhouse gas emissions by at least 1.2 million metric tons. That’s roughly equivalent to taking nearly 260,000 passenger cars off the road.

However, fuel made from switchgrass grown on the wrong type of soils actually releases more greenhouse gasses than gasoline, according to the paper published in the journal GCB-Bioenergy.

That data should be used to guide policy decisions about where energy crops should be planted to achieve the best results, said Bruce Dale, a professor of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science at Michigan State University and coauthor of the study.

“We should not underestimate the potential of these marginal lands,” Dale said. “Neither should we be blind about some limitations.”

Advanced biofuels made from non-food plants are a key component of the Biden administration’s plan to decarbonize the transportation sector, the nation’s largest source of greenhouse gasses, as they will be needed to power airplanes and other vehicles that can’t be practically run on electricity as well as millions of older internal combustion vehicles that will still be on the roads after 2040.

A perennial grass native to North America, switchgrass does not require a lot of fertilizer and grows quickly in a variety of climates in poor soils that aren’t suitable for food crops.

Researchers at the GLBRC are working to develop cost-effective methods for breaking down the plant into components that can be turned into alternative fuels as well as chemicals that can be made into products like nylon and polyester.

The new paper, which Dale describes as the capstone to 15 years of research, shows that switchgrass can slow climate change by pulling carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in soil, so long as that soil is not already full of carbon.

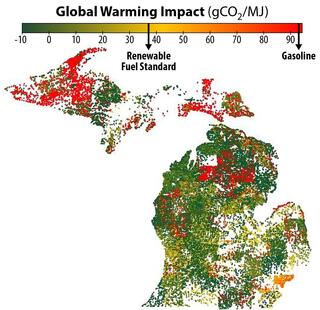

Dale and his colleagues used computer models to simulate the yields of switchgrass planted on unutilized agricultural lands in Michigan under varying conditions. The study assumed three plantings over 30 years and evaluated yields with and without nitrogen fertilizers.

They found that Michigan’s marginal lands could grow enough fertilized switchgrass to produce more than 150 million gallons of sustainable biofuel per year.

Almost all of that fuel would meet the federal Renewable Fuel Standard guidelines of 60% lower lifecycle emissions than gasoline. About three quarters of that biofuel would be carbon negative, meaning the switchgrass would add more carbon to the soils than is released by burning the biofuel.

However, the study found that only happens in soils with low fertility.

In soils that are already saturated with carbon, such as wetlands, Dale said the disturbance of planting releases more carbon into the air than the switchgrass can replace. As a result, biofuel made from plants grown on those lands has a higher global warming intensity than fossil fuels.

Fortunately, only about 11% of Michigan’s marginal lands contain this carbon-rich soil, meaning there’s plenty of good places to grow switchgrass.

The challenge now is developing cost-effective methods for converting switchgrass and other non-food crops into the chemical components of fuel and chemicals.

“We know that switchgrass can be grown at large scale as a carbon-negative biofuel feedstock,” Dale said. “But what we don't have in place is a system to transport the switchgrass to large-scale biorefineries where the biomass can be converted, also at very large scale, to replace fuels currently derived from petroleum.”