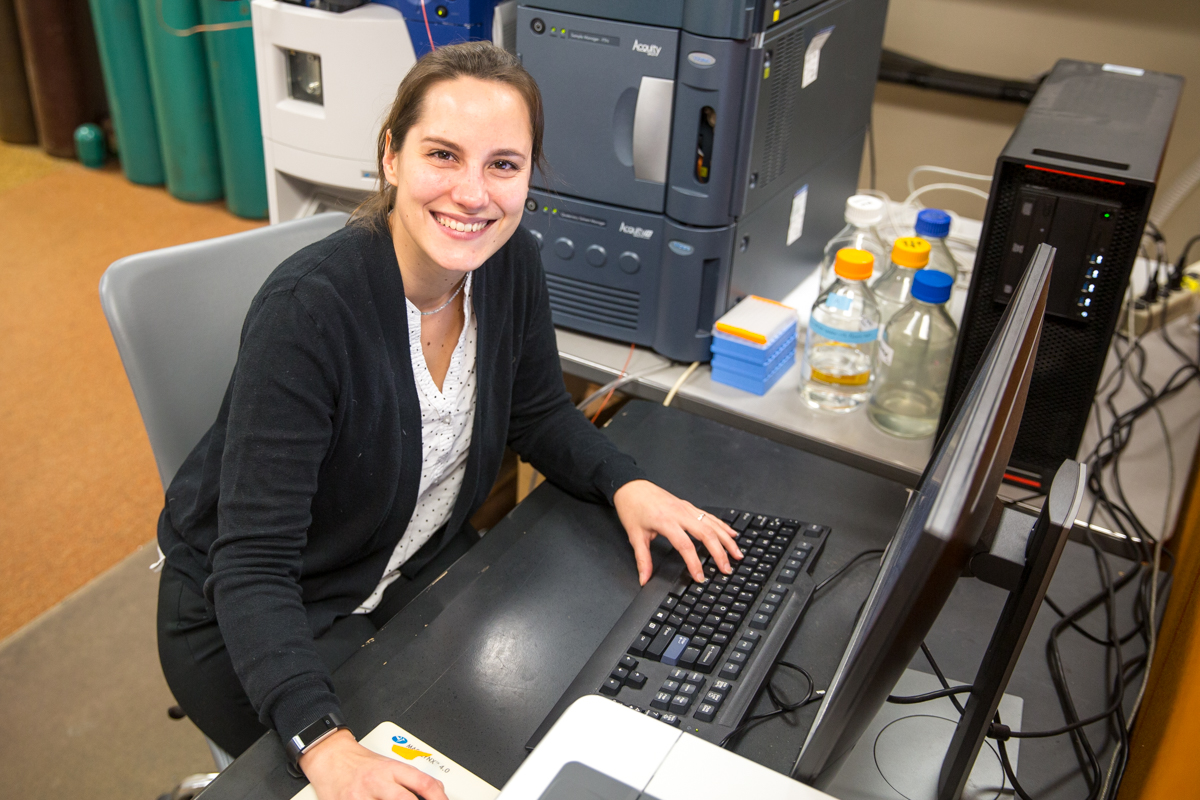

Anne-Sophie Bohrer, Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC) postdoctoral research associate at Michigan State University (MSU), specializes in resilience. Originally from France, Bohrer moved to the United States after her PhD to study plant metabolism at MSU and now researches the metabolic makeup of switchgrass with GLBRC.

During the first year of her Master’s degree in France at the Pierre and Marie Curie University, Bohrer spent three months interning in a laboratory measuring stomata to better understand drought response in Arabidopsis.

“When everything works it’s great, but it’s really rare that everything you do in a lab works,” she says. “At the time, I didn’t think of myself as someone who would be able to do an experiment every day for weeks or months at a time and still be willing to do it.”

But despite her preconceptions, Bohrer quickly adapted to the everyday routines of a lab career.

“I think from there I really learned how to be resilient, because it’s not easy” she said.

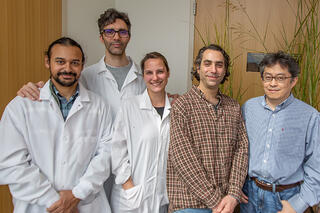

Since its founding in 2007, scientists at GLBRC have pursued a common goal: developing biofuels and bioproducts that are both environmentally sustainable and economically viable. Twelve years of trial, error, and promising discoveries later, our researchers continue to collaborate to design the most efficient bioenergy refinery and agricultural systems yet.

Bohrer and the team she works with are interested in maximizing the yield of switchgrass, a promising bioenergy crop that requires low inputs (nutrients and water) yet can accumulate high biomass in places where corn and other crops might not flourish.

Best of both worlds

Northern cultivars of switchgrass are well-equipped to survive cold winters, but accumulate less biomass than their southern cousins. Southern cultivars of switchgrass, however, have little tolerance to cold and freezing temperatures.

One of Bohrer’s projects is to study the divergence in cold tolerance between northern and southern switchgrass cultivars. Bohrer’s work focuses on the study of the primary metabolism, which encompasses a wide variety of compounds (i.e. metabolites) essential for the growth and development of the plant. Many of these compounds are known to be involved in protecting the plant against environmental stresses, including freezing temperatures.

“The overall goal of this study is to identify genetic markers and metabolic traits that would explain how northern and southern cultivars of switchgrass evolved differently and adapted to their respective environment, leading to a divergent tolerance to cold stress” she explains. “Ideally, we want to have varieties of switchgrass that flower as late in the season as possible to accumulate high amounts of biomass, while having them resist extreme environmental conditions.”

Collaboration is key

Bohrer says an emphasis on collaboration is one of the most important values that a scientist could possess. “Even though each lab works on their own specific projects or tasks, it is always clear that our work is connected through the mission of the GLBRC.”

“I personally work with the plant itself to eventually make it the best it can be for the production of biofuels,” she explained. “But at the same time, I know that what I do will have an impact on how colleagues focusing on breaking down plant matter will approach their research as well.”

Bohrer says collaboration will continue to play a large role in her vocation, and not just when it comes to her colleagues.

In fact, cultivating new scientists is something that Bohrer is incredibly passionate about.

“I see my role in the lab as an educator for the new generation of students” she said. “And what I am more and more attracted to is helping students thrive in the career that they choose to pursue.”

“I love to help them not just be good scientists, but also be good communicators and leaders,” she says. “I think it’s really important for people to see that scientists are normal people, too.”

Bohrer has learned a lot about resilience from her years in the field. Now, she works to develop resilience in the plants she studies as well as the students she mentors.

“This is really why I like science,” she said. “It gives us the tools to overcome hurdles when we’re facing this thing that seems to be unresolvable. Eventually, there’s always a way around it.”