Over 400 scientists, students and staff drive GLBRC research. In the profiles below, you’ll hear from four scientists representing our Deconstruction, Conversion, and Sustainability Research Areas, each of them focusing on a different part of the pipeline that turns cellulosic biomass into ethanol and other advanced biofuels.

Tell us a little about your research:

At the Arlington Agricultural Research Station, just north of Madison, I work with Chris Kucharik and Randy Jackson, my two co-advisors. We are looking at the ecological sustainability of biofuels. In particular, I am focusing on the perennial grassland crops, such as switchgrass, a mix of native grass (such as big blue stem and indian grass), and prairie (which has flowers and grasses in it). I’m investigating nitrogen cycling with these grasses. More specifically, I’m trying to determine how plant diversity affects emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide.

What contribution would you like to be able to say that you’ve made to your field in the next ten years?

I would like to say that I’ve added some piece of the puzzle to sustainable agriculture, or sustainable biofuels. No one person can say that they’ve solved the whole puzzle, but it’d be awesome if I could contribute a piece. Also, I’d like to help make a bridge between the scientific community and the public, whether that means farmers or the voting public as a whole.

What advice would you give to an aspiring scientist?

I would tell him or her to get into a science lab, especially if they are at a research university like UW-Madison. You learn a lot more in a lab than you ever can in a classroom. Going to work in a lab was one of the best decisions I made as an undergrad. Even though I ended up switching out of my first lab and completely changing majors, I learned a lot from the experience. I learned that I didn’t want to study in that field, and I also learned about the scientific process and how labs work.

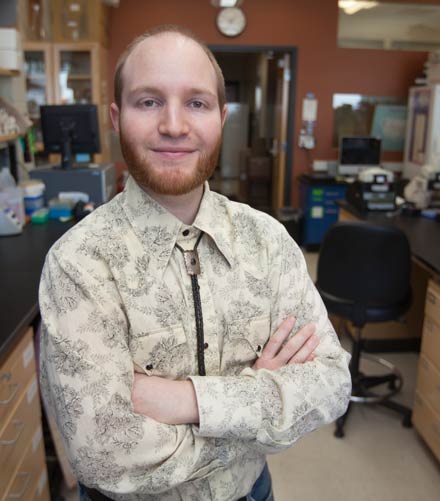

At the GLBRC/KBS long-term ecological research (LTER) site, Laube explores nitrogen recycling as part of GLBRC’s work on sustainability. Photo by James Tesmer, GLBRC.

Where did you earn your degree(s) and what did you study?

I obtained my master’s degree in Biochemical Engineering at the Nanjing University of Technology in China in 2008. Then, I came to Michigan State University to pursue my Ph.D. degree in Chemical Engineering and joined Professor Bruce Dale’s group and started to work in the GLBRC. I finished my Ph.D. study in May, 2012 and have continued working in the GLBRC as a postdoc.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

When I was a kid back in 80s, people around me liked and talked about scientists more than movie stars.

Tell us a little about your research:

My current research focuses on process engineering for integrating and optimizing biomass conversion process including enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation.

What does your typical day in the lab involve?

I discuss and design experiments with my technician and undergraduates, write manuscripts and read literature, discuss scientific questions with my colleagues, perform some experiments and reply to emails.

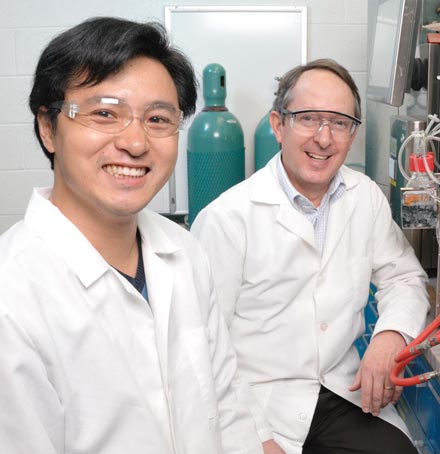

Mingjie Jin (left) and GLBRC Deconstruction leader Bruce Dale in the Biomass Conversion Research Lab (BCRL) at Michigan State University. Photo by Harley J. Seeley, MSU.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

The first time I really felt science was my calling was in high school biology. I was sitting in class and the teacher was talking about human genetic diseases. When he talked about muscular dystrophy, I immediately perked up, because muscular dystrophy runs in my family. After doing the math, I realized that because my mother’s brother had had the disease, I had had a 25 percent chance of having the disease and never making it to age 16. Clearly I didn’t have the disease. That moment was so amazing to me, just that there are these big things in the world, and we can understand them. We can talk about them, we can predict them, and we can even control them. That made the idea of science seem both very powerful and very attractive to me.

What is that strangest object located in your workspace?

A framed picture of an agarose gel. This picture reminds me that it’s worth persevering and trying things, even if they seem like they’re not going to work. Shortly after I started at the GLBRC, I was talking to one of my supervisors about wanting to clone this unusually large section of DNA. He said that the normal method wouldn’t work. A week later, that second step had worked, and the process was complete! This photo shows the gel that I cut up, and in which I was able to prove it had all the pieces of DNA that I wanted to have in it and it was exactly what I was trying to make.

Postdoctoral researcher Rembrandt Haft’s research focuses on increasing E. coli’s ability to efficiently convert biomass to ethanol.

How were you introduced to fermentation as a field of study?

During my graduate research, I joined a lab at the Chinese Agricultural University, which had some of the best fermentation equipment in China at that time. I joined this lab because of my interest in bioenergy research, but I was especially happy to do so because fermentation is actually one of my favorite things to do.

What is your role at the GLBRC?

I am the head scientist of the Experimental Fermentation Lab, which is a component of the GLBRC’s Microbial Synthetic Biology Laboratory at UW-Madison.

The lab examines the performance of engineered microbes used to convert biomass into fuels, while looking for ways to improve their performance.

Other labs may look at different materials used to produce fuel, but our lab focuses on fermenting cellulosic biomass to produce ethanol. Our lab’s work is important because microbes can behave differently at different volumes. A microbe might ferment very well in a small flask, but poorly in a large fermenter. This complicates our work, because we work at small scales, but our ultimate goal is to find microbes that perform well at a large, industrial scale.

Zhang and Alex La Reau in the Experimental Fermentation Facility, part of the Center’s Conversion group. Photo by Heather Heggemeier, GLBRC.